Smokey Hollow Community

Historic American Landscapes Survey

Blueprint 200 Joint Tallahassee and Leon County Certified Local Government

Link to documents in the Library of Congress: http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/fl0781/

Link to “Smokey Hollow: Tallahassee Remembers its African American Heritage with HALS Documentation,” David Driapsa, The Alliance Review, National Alliance of Preservation Commissions. [BEGIN PAGE 32]. https://www.z2systems.com/neon/resource/napc/files/TheAllianceReview_Fall2015_Final.pdf

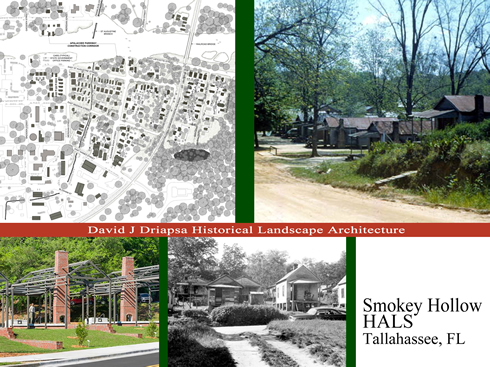

David Driapsa led the Smokey Hollow Historic American Landscapes Survey, conducting archival research and oral histories with former residents to record the historical narratives of government eminent domain in the mid-twentieth century on an established Tallahassee, Florida, African American neighborhood.

Congress established the Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS) in 2000 to provide a process for the systematic documentation of historic American landscapes. HALS records historic landscapes in the United States and its territories through measured and interpretive drawings, written histories, and large-format photographs.

From the end of the Civil War to the 1960s, Smokey Hollow was home to a racially segregated African American community in Tallahassee, Florida. State government removed houses, stores and churches to make-way for post-World War II state capitol urban renewal projects. As part of a twenty-first century project to redevelop the area into a community park through the project titled the New Cascades Park, the city of Tallahassee tells the story of Smokey Hollow through spirit houses, interpretive signs, and this Historic American Landscapes Survey. Documentation produced by David Driapsa and his team of scholars provided the crucial foundation for the commemoration.

Government intervention displaced this vibrant racially segregated community. Through the power of eminent domain, the state of Florida eliminated most of the housing and business structures that had existed in Smokey Hollow since before the turn of the twentieth century. Yet, that dissolution did not eradicate the community’s sense of itself. This is the story of the development of this African American community, its dissolution, and its persistence in memory after dislocation.

Although a system of segregation limited opportunities, African Americans refused to let those restrictions define them. Starting in the 1890s, members of Smokey Hollow began building a community identified by families, social organizations, cultural institutions, and businesses. Over the course of the next sixty years, the neighborhood became tight knit.

At the same time, the late arrival of residential zoning ordinances, the absence of legal minimum standards of housing, and a hilly topography shaped the contours of the built environment. Vernacular structures, most often made of wood, most often one-story, and most often owned by white non-residents, dominated the landscape. In contrast to improvements in infrastructure in predominately-white communities in Tallahassee, in the late 1950s, most of the roads in Smokey Hollow were still unpaved and many residents lived without basic urban amenities. In addition, an unprotected water ditch and a railroad ran through the area.

Yet, until the call to redevelop the area around the state capitol to house an expanded government courtesy of the state’s post World War II growth, few politicians took notice of the area. In an era when most African Americans were disenfranchised, Smokey Hollow fell vulnerable to the call for urban renewal.

The move to acquire the land for state offices in the early 1960s forced residents to disperse into other African American neighborhoods. The majority of Smokey Hollow’s residents lost their homes and their businesses. Yet, in their diaspora, former residents persevered in maintaining the memory of Smokey Hollow in the remnants of that community’s physical manifestations, reunions and other commemorative events.

This HALS captures the archival history and private memories of Smokey Hollow and consecrates them as a public memory. It makes the community’s former presence on the landscape perceptible to those in the present.